RubyFrontier Documentation

The hierarchical structure of non-directive folders and page object files has two simultaneous meanings in a RubyFrontier source folder.

|

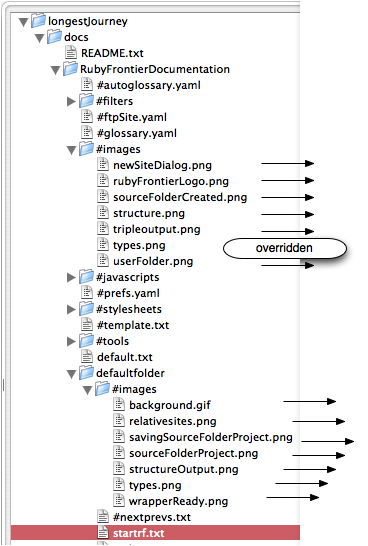

| Figure 1: A typical source folder. |

Physical meaning (Web site layout): As I already said, the hierarchy of non-directive folders and page object files in the source folder will be mirrored into an identical hierarchy in the resulting Web site.

Conceptual meaning (directives): When a page object is processed, the first thing that happens is that RubyFrontier walks the hierarchy upwards from the page object, looking for directives (and gathering them into the page table), starting with the folder that contains the page object. Most directives can be located anywhere in the source folder. So, as RubyFrontier walks the hierarchy upwards, it might encounter the same directive more than once (because the directive is present both in a folder and in another folder that contains it).

Indeed, you can see that this will happen in Figure 1. When the file

executet.txtis processed, no directives are found in the folder that contains it (breakpoifolder). But as RubyFrontier walks up the hierarchy, a#nextprevs.txtdirective will be found in the folder containing that (debugfolder). And than another#nextprevs.txtdirective will be found in the folder containing that (developfolder). And so on until we reach the top level and encounter all the rest of the directives.

Now, if RubyFrontier encounters just one copy of a certain directive as it walks up the hierarchy, there’s no problem. But you need to understand what happens if RubyFrontier encounters more than one copy of the same directive. There are actually two different rules for what happens:

In most cases, the first copy of a directive encountered will be the one that counts.

So, for example, in Figure 1, the only

#nextprevs.txtthat will apply whenexecutet.txtis rendered is the one indebugfolder; copies of#nextprevs.txthigher up the hierarchy will be ignored. In other words, the directive that counts is the one closest to the page object being rendered.

This means that you can use the folder hierarchy to give different renderable page objects different behavior. Thinking about it, you can see that all page objects in any folder at any depth share all the directives at the top level, unless a directive is overshadowed by a same-named directive at a lower level closer to a particular page object.

For instance, in Figure 1, all page objects share certain behavior dictated by the directives at top level, but some page objects at lower levels have a

#nextprevs.txtdirective that overshadows the#nextprevs.txtdirective at higher levels.

In general, you can use the hierarchical structure of a source folder, by means of a folder and the directives that apply to it, to give a group of Web pages a similar appearance, as opposed to other pages outside that folder.

In certain special cases, a directive is “folded” into same-named directives encountered higher up. This means that the directive’s contents override the contents of same-named higher directives, but the directive itself does not override.

For example, an #images folder has folding behavior. Suppose there were an #images folder inside breakpoifolder. Then any image files inside it would be incorporated into the images directive, but higher-level #images folders, like the one at top level, will not be ignored: any image files inside them will be incorporated into the images directive too. That’s “folding”. However there is still overshadowing, in this sense: if the #images folder inside breakpoifolder contains an image file called types.png and the #images folder at top level also contains an image file called types.png, the second one (at top level) will be ignored.

|

| Figure 2: An example of directive folding. When startrf.txt is rendered, two #images folders are found. The images in both folders are available, except that the image “types.png” in the lower folder overrides the one in the higher folder. |

(For another example of how folding operates, see this page.)

This documentation prepared

by Matt Neuburg, phd = matt at tidbits dot com

(http://www.apeth.net/matt/),

using RubyFrontier.

Download RubyFrontier from

GitHub.